MODULATING JAMS OF SUMMER 2015 - PART 3

[Editor's Note: We welcome back phish.net contributor and musicologist Mike Hamad, who shares his thoughts on the "Modulating Jams of Summer 2015." Below is the last of three parts. Part 1; Part 2. -PZ]

Compound MODs: My Double Wants to Pull Me Down

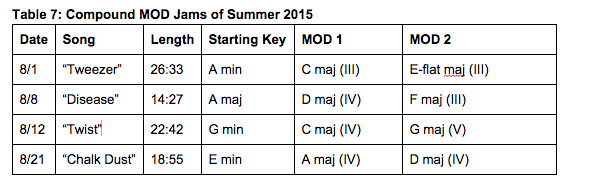

Four jams this summer modulated twice before calling it quits. I’ve been referring to these jams as double – or compound – MODs. They function by simply combining two of any of the four MODs (III, IV, V and flat-VII) discussed previously. These also happen to be monster jams; technically, they are the four most harmonically adventurous jams of summer 2015.

Table 7 lists the four Compound MOD jams Phish played this summer:

Pathways: the 8/1 “Tweezer” jam was the only compound MOD III-III of the summer, moving from A min (5:52-9:51) > C maj (9:51-23:46) > min > E-flat maj (2:47), which led right into “Waiting All Night” (also in E-flat). Also notable: two simple MOD IIIs stuck together takes you a tritone distance (i.e. A > E-flat) from where you started.

After a long tonicization of F# (vi), the 8/8 “Disease” jam turns into a compound MOD IV-III jam, moving from A maj (4:44-10:46) > D maj (10:46-12:35) > min > F maj (12:35-14:27). This MOD IV is more the blissful type – more like a MOD III in spirit than a “gear-shifter,” as in the 8/22 “Caspian.”

The harmonic trajectory of the 8/12 “Twist” – a compound MOD IV-V jam – is from G min (2:27-6:03) > C maj (6:03-13:06) > G maj (13:06-22:42). It returns, in other words, to its starting key (G), but in a different mode. Several times during the jam, you can hear Mike try to return to the “Twist” motive, with little support from the others. The first MOD IV comes after an aborted tonicization of III; there’s often some searching that goes on before travel plans stick.

Finally, the Magnaball “Chalk Dust” (8/22) is a compound MOD IV-IV jam, one that keeps moving toward the flat-side of the circle of fifths: E min (6:08-7:34) > A maj (7:34-15:14) > D maj (15:14-18:55).

"Tweezer" – 8/1/15, Atlanta, GA

Honorable Mentions

Eight additional jams contain modulations that don’t hit the two-minute mark, usually to set up segues. Table 8 shows how long these MODs stayed there, and where they went. You’ll notice the subsequent songs (“segues into”) are all in the exact keys of these brief MODs. When I examined this group, it became clear that these weren’t true MODs; they’re more like ways of patching set segments together.

You may notice that the famous Nashville “Mike’s Song,” which marked the return of the second jam, didn’t even make it to Table 8. Each of the two separate jams, the first in F# minor and the second in F minor, as structural components; each begins and ends in the same key, without modulation. If one jam began in F# and moved to F, without being segmented by the band, it would be a different story.

Putting it all together

“Tweezer” -> “Caspian” nicely demonstrates two different approaches to the key of C major: the first, a sort of blissful settling-in (the MOD III in “Tweezer”) and the second, a ramping up toward an eventual peak (the MOD IV in “Caspian”). Yet, through it all, C major is C major is C major.

For many, the high point of the summer came at Magnaball during Saturday’s second set, with the 30-minute pairing of “Tweezer” and “Prince Caspian.” Taken as a single entity, “Tweezer” -> “Caspian” could be considered one monster compound MOD jam (III-V-IV, moving from A > C > G > C).

At 7:52 of “Tweezer” – a moment where the jam dips and blisses out (Page’s Rhodes is prominent, along with Trey’s ambient effects) – they modulate from A min > C maj (MOD III). Plenty of dissonance follows, up to around the nine-minute mark. Then, when fully committed to C major, the rest of the jam is all about introducing new chord progressions and staying on an upward dynamic slope. In the final minute Fishman all but drops out, and Trey tonicizes (“makes home”) G major (V in C), and that leads the way to “Caspian.”

4:48 into “Caspian,” Trey and Page start flipping the mode from G maj > min, leading to what many hear as return to “Tweezer” (Charlie Dirksen called this “a ‘Tweezer’ jam in the key of ‘Fuckerpants’”). They jam in G minor for another nearly eight more minutes (4:48-12:20) before a scorching MOD IV into C major–the same C major we heard in “Tweezer,” only different, more fully alive, shifting into high gear the high gear of your soul.

"Tweezer" > "Prince Caspian" – 8/22/15, Watkins Glen, NY

Where do they go?

The reason I started looking into this stuff in the first place: while listening to the 9/6 “Carini” in real-time, I heard a move from E min > A maj (MOD IV) only seventeen seconds into the jam. That’s unusual.

Like others on Twitter at the time, I called “Tweezer” (A min). But that would have been too easy; six minutes (of A major) later, I realized: they aren’t going into “Tweezer.” That’s too much time in A (major or minor), assuming a long “Tweezer” jam would likely follow the song-part.

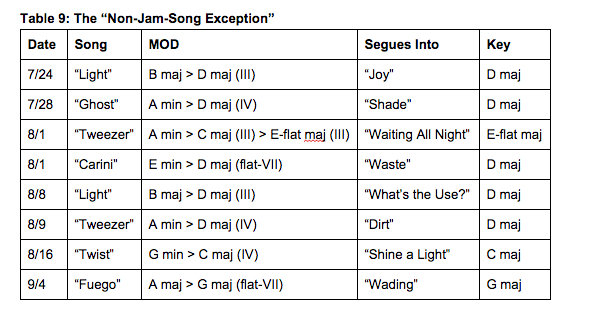

Which led to a general principle I’ve stumbled onto when segueing out of modulating jams. I call this the “non-jam-song exception”:

- if they’ve jammed for a long time in a certain key (i.e. A major in the example above), they generally are not going to segue into a jam song in the same key.

- they can (and often do), however, segue into a non-jam song (“Joy,” “Shade,” “My Friend,” “Waiting All Night,” “The Line,” “Bug,” “Dirt,” “Wading,” “Waste,” “Lizards” etc.). The modulating part of the jam, in these cases, is a sort of pre-jam, tacked on before a non-jam song.

Table 9 shows how modulating jams segue into non-jam songs in the same key:

Naturally, there are other exceptions – long, modulating jams that do segue into other jam songs in the same key.

- After a MOD flat-VII from G minor to F major, the 7/31 “Twist” gives us six long minutes in F major before a segue into “Back on the Train” – arguably a jam song – in the same key.

- As noted earlier, the 8/7 “Chalk Dust” serves up seven whole minutes in A maj before the subsequent (excellent) segue into “Tweezer,” a jam song that’s also in A. (I feel confident the E > A > E sandwich created by the two songs makes up for it.)

- The 8/21 “Ghost,” which moves from A min > C maj (MOD III) leads to a jam song – “Rock and Roll” – that’s also in C major. (Many people online expressed their displeasure with this segue.)

- Similarly, the 8/22 “Blaze On,” after modulating from C# > E maj, stays there for six-and-a-half minutes before segueing into “Possum,” (arguably) a jam song that’s also in E.

- The final set at Magnaball served up a whole lot of time in the same key: the 8/23 “Disease” moved from A maj > D maj (MOD III) and remained there for more than six minutes before segueing into “Scents and Subtle Sounds” (also in D, and arguably a jam song).

- The 9/6 “Chalk Dust” spent 8.5 minutes spent in G maj before segueing into “Twist” (in G minor).

Conclusion

Before we go touting the harmonic adventurousness of the summer 2015 tour, it’s important to remember the 7/13/14 “Chalk Dust,” which went all over the place: E min > D maj > F# min > E-flat > F > D-flat, before landing in B major (for “Light”). If you squish it all together within the space of an octave (and switch every flat to sharp), that’s C#-D-D#-E-F-F#, or the entire chromatic set between C#-F#. They spent time, in other words, in every tonal area in the span of a perfect fourth. That’s craziness. Nothing in 2015 even comes close.

You can – and should – enjoy Phish jams without thinking about or hearing modulations. For me, new keys and modes are like colors changing in front of my eyes. I can’t ignore them. They’re as real as anything else I experience at a show. It’s not something I can shut off.

But I’m happy knowing that very few other bands change keys and modes spontaneously during jams the way Phish does. (The Grateful Dead didn’t.) You can take the methodology I’ve outlined in this article and back it up through 3.0, to 2.0 and 1.0, as a way of measuring how truly exploratory this band was during a given era or tour. It’s a ton of work, but it’s totally worth it.

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.

The Mockingbird Foundation

The Mockingbird Foundation

I'd be curious to get your take on earlier periods of Phish jamming, specifically '92 - '95. While the band did modulate jams at this point, it seems to me that a bigger aspect of the jamming back then compared to '97 thru to now was rhythmic changes. For example, in a Bowie, Antelope, or SOAM back then, you have frequent brief rhythmic change ups that seem less common today. At that time, Trey was clearly still driving the jams, and Fish seemed keenly dialed in to Trey's sudden and abrupt suspensions or other temporary changes to the underlying rhythm. I sort of think of this period as a time when the band (or at least Trey) was still considerably under the influence of Frank Zappa's compositional style. With the more cohesive, band-wide jamming that emerged in 1997 and on, it seems that sudden rhythmic changes are more difficult to pull off without a clear leader. On the other hand, the modulation of key, as you clearly note, can be signaled by one band member, and adopted by the others once Mike buys in to the change. Anyways thanks again for the great and detailed lesson in Phish music theory.

Calkdust at MagnaBALLS was amazing!

But that thing about the Chalkdust from last year, that's just completely insaneballs

As a fellow player and half-arse theorist, I would add that for me, the beauty of Phish is in the HOW. Their many years of exploring playing as a unit continues to pay off huge in this area. These guys have always been listeners first to me, and players second. Playing music that modulates, whether it is composed or improvised, is very hard, and takes special care to do so in a natural manner. It is akin to a speaking language. Anyone can learn the word 'antiestablishmentarianism', but only very few can use it effectively in a live conversation. These guys do it with apparent ease and grace. I've seen other bands attempt these types of ensemble harmonic shifts (Panic comes to mind, sorry), and they come off as clunky or belabored, at best, if not down right jarring. The CDT example from 7/31/14 was especially enlightening. Wow!

Sounds like you enjoy the legwork on this too, so I look forward to future tour reviews!

Cheers

Take "Playing in the Band," for example. Almost every version stays pretty squarely in D for most of the jam. There are occasional modal shifts by Jerry (to G mixolydian, for example, or A minor), and little asides to other chords from Bob, but the overall harmonic realm remains in D. In my opinion, the sense of travel and exploration comes from the different way that the Dead filled that harmonic space with melodic material, and also with noise. Noise is a huge part of the Dead's pre-hiatus sound that's not as prevalent in Phish.

There is a musicologist named Graeme Boone who has systematically gone through every single "Dark Star" from its debut through 1969 (I think that's as far as he's gotten) and has also done this for "Bird Song" from the early 70s. One of the fascinating things that he shows is that within these jams there are spaces that the band travels through and around, but it tends to remain contained within a harmonic space. The beauty comes from the swirling coloration of melody and harmony contained within a general tonal space (in the case of "Dark Star," for example, A). The beauty of these modulating Phish jams comes from their ability to journey along tonal pathways. That's why even though the Dead and Phish are often compared, and their approach to improvisation is philosophically similar, the actual end result can be very different.

So, can we get the info from this article into the Jam Charts?! Holy crap.

Can we use this analysis to compare Phish jamming over the years? Will you be able to execute the same analysis for some other concert stretches, like August 93, December 97, 2002, Fall 2013?

What about other metrics, like TEMPO and rhythm? Well you can't ignore the modulations (I can't either, but I don't have good pitch recog skills), I doubt any of us can ignore rhythm and tempo shifts. How often do they intermingle? I assume most jams are in 4/4 or just get too loose to matter. I would learn a lot from that sort of analysis too.

Ultimately, all that data could feed into an index. It would a scientific metric of a jam's quality. Like a point system. It would be freaking cool and I think we could geek out this. Like image if the indexes were added up over the concert and each night could be analyzed and scored. We could place bets and stuff, or we could have like a fantasy game where we pick songs for the tour and ... you know where this is headed, right? We got a good game in the making here!

Your article gave birth to some epiphanies for me. The MB Tweezer> Caspian now makes so much more sense. I felt that they went back into a "Tweezer jam" but didn't know what made it so. Now seeing that they returned to the same key as the Tweezer jam, I understand.

Though I'll likely never be able to hear these modulations with any regularity, being a non-musician, I can certainly try. I think that will make relistening to the big 2015 jams even more enjoyable. Thanks again.

My only criticism is that as I am not familiar with music theory, quite a bit of part 2 went over my head. I do think it could have been presented to those of us who don't have that background a bit more clearly, but I still took a lot away from this piece as a whole. Maybe more examples would have helped. Listening to the Blossom CDT> Tweezer with your notes was a big help.

If you can assume - as you said in a comment - that all "minors" are Dorian and all "majors" are Mixolydian then I guess that clears it up, but it also raises some other questions. For example, when you see a MODIII jam like the 8/1 Tweezer going from what you call Amin to Cmaj it seems more plausible that this would be a move from Aeolian to Ionian (relatives), and not from Dorian to Mixolydian since C-Mixolydian (C-D-E-F-G-A-Bb) would use a different set of notes than A-Dorian (A-B-C-D-E-F#-G).

Would anyone be interested in a book of this type of analysis?

Obviously they don't have the kind of depth as Phish in their improvisation, but what they DO have is a consistent dedication to segueing - at high speed and high volume- into songs in different keys. And their approach to it is so methodical and mathematical that you can anticipate it. A lot of "And now this note changes, and then that note changes, and then that note changes, and now we're all hitting this same chord at the same time"

It's simplistic, but devestatingly effective to have that "Shift into the Bowie ending" in every song.

@MikeHamad said: Absolutely!

1) The common MOD to bVII seems to be a byproduct of Trey/Mike treating the major and mixolydian modes as interchangeable. When the band is in a major-key 'rock' jam (basically anything that isn't Reba/Wingsuit lydian bliss or phrygian/middle-eastern stuff like Taste/Limb By Limb/Light), the ^7 and ^b7 are usually treated as equal. I suspect this is why moving from A to G in DWD is such a common occurrence. I also offer as proof of Trey/Mike treating major/mixolydian as equal the start of the jam in Slave: Mike almost always ignores the G major chord, playing around A, A, D, E, instead of Page/Trey's A, G, D, E progression.

2) Why do you think the band so frequently goes from i to III, but rarely I to vi? It seems like the only way they move to minor keys is through mode mixture (I to i) or an abrupt move which is ill-prepared (i.e. Trey just starts playing a D minor chord because he wants to play some song in D minor next!). I can't think of many jams where the band makes the MOD vi shift, but I can think of one famous time it was attempted by Mike: http://phish.in/1997-08-10/harry-hood?t=9m30s (Mike slightly modifies the Harry Hood jam: every second time through the D > A > G progression, he plays Bm > A > G). It sounds amazing, but I can't think of any other times off the top of my head that this has happened. Why might the band avoid MOD vi? It seems to me (as a bassist), that moving there would be quite easy, and I have no doubt that it's as easy as MOD III. Just a curious observation.

3) Since most MODs come from Mike and Trey, do you think they consider the playability of the new key for Page? As you know on guitar, moving from one key to another is kind of a cakewalk if you're not using open strings, but for keyboard players, moving too far too quick could be a pain. Perhaps this is why most MODs are relative major/minor, or one step away on the circle of 5ths? (MOD IV or V). I'd hate to be Page when the band is jamming in Eb, and then goes MOD bVII into Db major. "Thanks guys... this is great." *immediately moves to ambient washes on CS60/Rhodes* (Actually, I just looked up the Page gear video to get the name of the CS60, and stumbled across this exact quote: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1EyKV1wRvT8&feature=youtu.be&t=4m08s )

4) Finally, I suspect the reason that 555 hasn't taken off as a jam vehicle for the band is the awkwardness of that closing progression: Bbm > A. It doesn't fit any traditional key or mode, so it seems like Trey has a tricky time finding a real melody to put over it. He tends to rely on one bar phrases, then a bend over the tricky change, eliding the transition. It's almost like that song needs to do what Split Open and Melt does rhythmically. SOAM starts with that extra bar of 9/8 every fourth time through, but eventually the band abandons the rhythmic intricacy for an open jam, eventually returning to the original rhythm to signal the end of the jam. (I know it wasn't always like this back in the 90s, but since 2.0, that's basically been how it goes). 555 could do the same: Bbm > A for a while, then settle on one of those chords, and go deep. (The way Simple eventually settles on either F or Bb.) The problem seems to be that the Bbm > A progression doesn't leave enough melodic options open for the band to settle into a space where they can move into another jam in just Bbm. It goes around the progression for 2-3 minutes, then Trey realizes he's out of options, and hard segues into Light or something.

1) Totally agree. The major/mixo and minor/dorian are pretty much the standard pitch collections. You rarely hear any of them playing the natural ^7 or the flat ^6, right?

Much the same way there is no major II chord (it's a secondary dominant of V, or V/V) in rock music, the flat-VII chord is really just a secondary subdominant (IV/IV). I suspect its origin, which seems to have arrived with the rise of guitar-based rock music in the 1960s, has to do with the properties of writing music on the guitar itself, unlike writing on the piano, etc. That's a huge study for some to take on...

2) I wondered about that. I don't know of any jams that modulate in the opposite direction (I-vi). I really wonder why and have no clue. That's an interesting one you point out; I'm reminded also of Reba jams (a sort of never-ending IV-V progression, or E-flat to F, in some phantom B-flat key that isn't really there): sometimes Mike will go to G minor (vi in B-flat) and hang out there for a long time. It's worth exploring, though, if you've got the juice (do it!).

3) LOL. I wonder! Though I doubt they give it much consideration... I'll have to listen back to the Randall's Chalk Dust, which goes all over the place (including, I believe, to D-flat at the end...).

4) You may be right about that. I remember at the debut of 555, when they got to the jam, listening to Trey struggle to improvise over that B-flat to A progression; lately, though, he's abandoned that in favor of just playing in B-flat dorian/minor etc. Which is what he should do, in a sense, since that A is sort of just an altered dominant of B-flat (in an obscure kind of way). I can't imagine it's holding them back, since you're right: a la Melt, they could just ignore that alternation of chords and just go somewhere from B-flat. I think we'll see that eventually.

Also, in a subsequent email, we discovered a pair of MOD vi in the Dick's 2012 Light, at 6:50 and 15:37-16:10 (depending on where you want to drop the needle!) Interesting that this famous jam includes TWO of these rare modulations (rare for Phish, not for music), and yet the band seems reluctant to revisit. (Not a single MOD vi in 2015).

So while it's true that when Phish "jams" in A minor they are usually playing A dorian modes, it's still important to remember that we can't just exchange key and mode freely.

Great comments. It's common in these threads to hear comments such as "....the 'segue' from Sand to Light was jarring..." or something like that. Yet Light, for example, will almost always sound "jarring" coming out of ambience, regardless of key or tonality. The beginning of Light doesn't lend itself to segues. Just as you point out, many songs' endings don't lend themselves to easy transitions either. It's just a lot easier with vehicles like Disease and Ghost since there are so very many options with songs like that which don't offend the sensibilities when employed. Great comment on Panic as well. I hear the same thing and it's prevented me from every really embracing them. I'm spoiled I guess.